The Davis Mountains’ rugged terrain has helped protect it from human meddling.

By E. Dan Klepper

A most amazing phenomenon has occurred in the West Texas highlands surrounding Davis Mountains State Park. Aside from the addition of a few more fences, a cell tower, a scattering of new homes and businesses, and some black-top paving, time in this part of the state appears to have stopped. In fact, this cool, clear mountain country seems to have remained basically the same for the last 125 years. A testament to this paradox can be found in a passage from the journal of geologist Burr Duval, a member of an 1879 mineral expedition who described the region during his travels across the state.

“Certainly, under the light of a morning sun,” Duval observed, “this country is exceedingly lovely to look at — On my right some four or five miles are rough and rugged iron-colored mountains, on my left are hills of nearly equal height, smoothly sloping and gently rounded, covered to their very summits with the most magnificent grasses, which even now look cured and not dead — Before me lies a gently undulating valley miles in extent … Not a living thing is in sight except a herd of antelope in the West — perhaps a mile away.”

Duval’s description may sound idealized and old-fashioned, but the fact is that this Davis Mountains observation could have been written yesterday. Remarkably, visitors to Davis Mountains State Park can still embrace Duval’s morning mountain beauty with their own eyes. More profoundly, Texans can hike across the park on one of its several well-groomed trails and experience what Duval considered the heartfelt consequence of traveling through Texas’ high-elevation countryside.

“We are among the Sierras now,” Burr exclaimed, “not the ‘Mesas’ any longer, and indeed are touching the backbone of the continent.”

Backbone is an apt analogy for the Davis Mountains and its geography of palisade walls that arise everywhere like the vertebrae of some extinct and unknown creature. The mountains were formed around 35 million years ago during a particularly violent period attributable to the eruptions of two massive volcanoes — the Buckhorn Caldera and the Paisano Volcano. These super volcanoes are estimated to have been eight to 10 miles in diameter — three times the size of Mount St. Helens. Evidence of their volatile nature is now characterized by the range’s rough canyons and exposed cliffs of magma intrusions, ash-flow tufts and lava. But seismic activity has not quite finished with the region yet. As recently as 1995, the surrounding West Texas sierra country experienced an earthquake measuring 5.6 on the Richter scale.

But none of this is daunting to the tremendous variety of wildlife that inhabits the range and often migrates through Davis Mountains State Park. The park is in many ways the epicenter of the Davis Mountains experience, providing visitors with an opportunity to settle comfortably in among canyon walls and catch nature’s antics. The range is considered a “sky island” where certain species have evolved here rather than any other place in Texas and, in some cases, on earth. Rainfall at its upper elevations of seven and eight thousand feet often exceeds by 10 inches annually that of the Chihuahuan desert floor below. The area has been lauded for the health and the preservation of its natural habitat which is due, in part, to the difficulty that humans have had in mastering its rugged terrain. But efforts to dominate its wilderness over the last 150 years have created quite an archive of Davis Mountains’ wildlife history.

“The Davis Mountains region was really wild in the Nineties,” historian and Davis native Will F. Evans wrote in his 1950s introduction to a collection of stories about the region. “When we first settled in the Davis Mountains in 1884 the bear were so very numerous that the women-folks made bread out of bear-oil; and the old Pioneers used deer and antelope meat for the table and the chuck-wagons. Panthers were so thick in the canyon in 1890 where the Evans ranch was established, that it was called Panther Canyon.”

Evans’ father, George Wesley Evans, and pioneer John Zackary Means were two of the first settlers in the region to try their hand at Davis Mountains ranching as well as big-game hunting. Friend and writer K. Lamity described the two gentlemen in an article for his 1924 Harpoon Magazine:

“Now they both have so many cattle they have to hire help to count them, and when they are not hunting bears and black-tailed bucks, they are both sitting out under the shade planning another hunt. During their first winter in the Davis Mountains they had no lard, but from the 65 fat black bears they killed that winter they had barrels of “bear-oil” — which beats lard for cooking. Added to this were antelope by the thousands, black-tail (mule deer) and multiplied millions of Top-Knot (Mexican) quail, as well as Bobwhites. In those days it was very stylish for cowboys to oil their hair and keep their boots well greased. George Evans told me that when they first got to killing bear, and hoarding the bear-oil, John Means became very extravagant — ‘bathing his top-knot with bear oil till it ran down and over-flowed his boots – saving labor, but wasting grease.’”

By mid-20th century the Davis Mountains’ big wildlife populations had collapsed due to unmitigated hunting and trapping, but the region’s landscape has remained relatively unchanged and is still ideal habitat for black bear, panther and antelope. Davis Mountains State Park has recorded at least two black bear sightings within the last 12 months, and one of them included a sow with two cubs. Mountain lion sightings in the park, while not routine, are still recorded occasionally. And efforts by area ranchers and TPWD’s wildlife division have helped to reestablish antelope populations within some of their historic Davis Mountains’ range.

Perhaps the most compelling wildlife the state park has to offer is its wide variety of birdlife. Historically, birders (like their subjects) have flocked to the Davis range because it excels in meeting their needs. As early as 1930, Davis historian Barry Scobee wrote reports for the West Texas Historical and Scientific Society about his birding forays into the Davis Mountains:

“In the summer of 1928 I had the privilege of being in the field with the late Otho C. Poling, noted entomologist and ornithologist,” Scobee wrote. “His ornithological knowledge embraced most of the known birds of North America, with their varied habits of feeding and nesting, and their songs and calls … In the previous article I listed seventy-four birds. Eleven more are listed here, making a total of eighty-five. And without doubt that is incomplete. Many birds come and go without being observed, and even a slight change in locale will reveal many new specimens.”

The gray-crowned rosy-finch, a species that ranges south only as far as Northern New Mexico, was among the birds Scobee spotted with Poling during that particular outing. It appears to be the only recorded sighting ever made of the bird in Texas.

“Mr. Poling discovered this in a thicket,” Scobee reported. “He said it was a bird that made its home chiefly in Alaska and that I might go a hundred years and not see another in Texas. It was not so large as a common sparrow, and it had some reddish and blue markings; it was a quick-flitting bird, and was soon gone.”

Scobee’s sighting of a rare or seldom-seen bird for Texas is not an unfamiliar event for birders in the state park. In fact, the count for resident and migratory bird species spotted in the park exceeds 250 to date. But the favored birding experience for most park visitors as well as some hardcore birders like TPWD Conservation Biologist Mark Lockwood involves one of the park’s most popular and frequently sighted residents.

“My fondest memory of birding Davis Mountains State Park involved the most famous bird of the park,” Lockwood recalls. “I was walking through the camping area in the spring of 1990 and came across a large covey of Montezuma quail (about 20 birds). I was able to watch and photograph them at very close range for about an hour as they dug up bulbs, took dust baths, and foraged through the grass. They would call back and forth and the males would occasionally give the long trilling call … a wonderful experience, and one that I will certainly never forget.”

Texans will find that accessing the abundance of natural history throughout Davis Mountains State Park is enhanced by the park’s interpretive center, an amphitheater and several organized programs.

“Our presentations at the park include nature hikes, bird walks, slide presentations on bats, plants and wildlife,” explains Park Superintendent John Holland, “plus cowboy history and historical programs by the Fort Davis National Historic Site.” In fact, cultural history also plays a vital roll in the park’s offerings, particularly when it comes to the accommodations.

The park’s Indian Lodge, the beautifully designed hotel and restaurant, was constructed in the 1930s by crews from the Civilian Conservation Corps and later expanded by TPWD in 1967. The lodge is an interesting chapter in the history of the CCC, a program introduced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and designed to put young American men back to work during the Depression. Once again, the park’s wildlife would prove to be a featured aspect of Davis Mountains’ history.

A CCC crew had arrived in the Davis Mountains in the summer of 1933 as members of one of several forestation camps, and the all-male crew was conscripted immediately to begin the first project for the newly established Davis Mountains State Park — the captivating “Skyline Drive.” The drive, now paved, offers park visitors a chance to take in the mountain views via an escalating switchback. Many of the young men who performed the back-breaking work took readily to the mountain air, spending their free time hiking in the area. While out exploring one day, several of the crew members came upon a bear cub and were able to capture it and return with the cub to camp. The crew christened the bear “camp mascot” — a short-lived title, as the bear quickly grew too large to handle, at which point the “mascot” was allegedly donated to the San Antonio Zoo.

Once the Skyline Drive was completed (although at that time it was still just a rough bumpy drive up the mountainside) work on the adobe bricks for the Indian Lodge began. The lodge opened in June of 1935 and was called The Indian Lodge Village. The designation “Village” was ultimately dropped once park officials discovered that visitors expected to see a village of Native Americans upon arrival.

The lodge’s architectural design is classic Pueblo Revival with accents that typify the CCC style known as Rustic. For Texans who prefer creature comforts and choose to forgo the excellent tent or RV camping opportunities the park has to offer, booking a room at the Indian Lodge is a great option. Either way, the park’s attractions, its cultural and natural histories and the Davis Mountains ambience add up to an outdoor experience unlike any other in Texas.

“Davis Mountains State Park is one of the only parks in Texas,” says Park Superintendent Holland, “with a mountain setting, great climate and unbelievable scenery.” If alive today, Burr Duval would no doubt agree.

“How deceptive distances appear,” Duval observed as he scanned the Davis Mountains horizon one morning in preparation to hunt deer. “… the air is so pure that a mile scarcely seems over a few hundred paces.” Duval may be long gone but, as luck would have it for all the Texans that have come after him, his Davis Mountains vision endures.

Excerpts from Burr Duval’s Journal of 1879-80 Expedition to Chenati Mountains courtesy of S. E. Maclin. Evans, Scobee and Harpoon excerpts courtesy Archives of the Big Bend.

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Search This Blog

My Mom

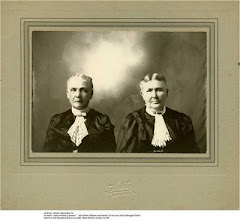

Sisters

Dad and his brothers

Grandma Carrie Ely

lived to be 94 years old

Jeanetta Koons and sister Margaret

Lana, Amber and Brandon Jenkins

"Bethie and Kevin"

Redone for "Bridges of Madison County"

Madison County Courthouse

Clarks Tower, Winterset, Iowa

In honor of Caleb Clark

Winterset, Iowa

"The Bridges of Madison County"

Spencer, Iowa

Home of some of the Callery's

Brownsville, Jefferson co, New York

Main street, 1909

Forefathers

An old Quaker Cemetery

Madison county, Iowa

Our Family Homes--Then and Now

Our Homes, some were lived in for generation, some for just a short time.

Musgrove and Abi Brown Evans Home

Musgrove Evans home

Musgrove Evans

The Ely Home est. 1880

919 Second St., Webster City, Iowa

Home of Jacob J. and Pamela Brown

Brownsville, Jefferson co, NY

Home of Pheobe Walton and Caleb Ball

, , PA

Villages, Towns and Cities of my family.

Some of the homes and places my family and extended family have lived.

See photos below the posts.

See photos below the posts.

About Me

- NeNe

- I am a very busy grandma and mom to a passel of kids! I love crafts and enjoy sharing with others. I am involved in several groups that have shared interests. I have been involved with lots of home make-overs and enjoy decorating for myself and friends.

Sword of the Border

Book on the life of Jacob Jennings Brown

No comments:

Post a Comment