The remains of Joseph R.T. Gordon, son of Major Jonathan W. Gordon, of the Eleventh U.S. Infantry, were interred at Indianapolis, on Friday, with impressive military ceremonies.

The remains were brought on by Cap. Patten of the 6th Indiana. [Ninth Indiana regiment, December 13] (Ninth regiment, December 13)

Full text of "A funeral sermon, on the death of Joseph R.T. Gordon, who was killed in the battle of Buffalo Mountain, December 13, 1861"

I hold it true, whate'er befall ;

I feel it, when I sorrow most ;

' Tis better to have loved and lost

Than never to have loved at all.

INDIANAPOLIS : JOURNAL COMPANY, PRINTERS.

My Dear Elgiva, Viola, and Eliza :

I dedicate to you this little memorial of

your dear brother Joseph. His love once filled our home and our

hearts with the light of happiness ; and his death has left us in dark-

ness and sorrow. His life was an act of devotion to duty, which he

warmed and brightened by the light of a love, as gentle and gener-

ous as ever gladdened the earth. He met his death in the sir-

cere endeavor of a true soul, " to act in a better manner the part

assigned " him, " in the great tragedy of life."

He is gone; but you will remember him — remember how he

loved you, and labored for your happiness ; and so love each other.

Learn from his beautiful life always to prefer duty to pleasure.

Learn, from his noble death, that it is better to die in the path of

duty, than to live out of it.

" Little children, love one another."

Your Father, J. W. GORDON.

J±

l/

FUNERAL SERMON,

ON THE DEATH OF

JOSEPH E. T. GORDON,

WHO WAS KILLED IN THE BATTLE OF BUFFALO MOUNTAIN,

DECEMBER 13, 1861.

DELIVERED BY

REV. A. L. BROOKS,

'•I

PASTOR OF THE

/

FOURTH PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH,

INDIANAPOLIS, IND.,

JANUARY 5, 1802.

EI SOU

"A plow is coming from the far end of a long field, and a daisy

stands nodding and full of dew-dimples. That furrow is sure to

strike the daisy. It casts its shadow as gaily, and exhales its gentle

breath as freely, and stands as simple, and radiant, and expectant

as ever ; and yet that crushing furrow, which is tearing and turn-

ing others in its course, is drawing near, and, in a moment, it whirls

the heedless flower with sudden reversal under the sod." — Selected by

Joseph R T. Gordon, from H. W. Beecher, as the first gem of a " Collec-

tion of things Useful and Beautiful, commenced July 18th, A. D. 1860."

SERMON.

DO THAT WHICH IS GOOD, AND THOU SHALT HAVE PRAISE OF THE

SAME. * * * * RENDER, THEREFORE, TO ALL THEIR

DUES ; TRIBUTE TO WHOM TRIBUTE IS DUE ; CUSTOM TO WHOM

CUSTOM ; FEAR TO WHOM FEAR J HONOR TO WHOM HONOR.

[Romans xiii., 3d, 7th.

The principal subject in these passages is unquestionably

the reverence and obedience of the Christian citizen for the

justly constituted civil Government. The Christian religion

imposes no duty more certainly than that of obedience to the

rightful authority of the State. It imposes that duty by the

solemn declarations of condemnation and wrath upon the dis-

obedient. But while these texts enforce the duty of a loyal

citizenship, they also assure us of the praise and honor that

are due, and shall be given to all those who do their duty.

There are circumstances, also, which will secure to the sub-

ject, who, with a pure and unaspiring loyalty, devotes his

powers to the preservation of the authority and prosperity

of the State, the special praise and honor of all good citi-

zens.

These simple truths premised, I now proceed to pay a trib-

ute of praise and honor to one of the youthful and beloved

citizens of this great and good Government, who has, in sin-

cere and disinterested patriotism, given his life, in the fearful

sacrifice of war, for the preservation of the Government

against a rebellion, in its irrational atrocities, unparalleled in

the history of the race.

Joseph R. T. Gordon was but a youth, not yet eighteen years

of age. He was no titled chieftain, on whose bronzed features

and stalwart form the scars and stars of war had become a

fixed habit. He had but little taste and limited discipline to

inspire him with martial zeal and courage. He was no titled

statesman, or famous civilian whom a heartless w T orld is so

proud to honor and follow. He was no marvellous genius of

the sacred or the sinning arts, to be embalmed in the songs,

or immortalized in the monuments of time. He was known

to but few; and by those but to be loved for his simple and

unostentatious virtues; — for his manly integrity and filial de-

votion; — clear and comprehensive intellect, and moral worth.

His hatred of wrong and oppression, and his patriotism were

no sinister and hollow-hearted boast of the aspirant for place

and power; but the diamond flashes of a soul fixed in the

golden settings of imperishable truth and right. He knew

no guide in his youthful zeal for the respect and love of his

kind, but conscience and truth. The tribute which we offer

to his memory at this time, is not the common and expected

service of an undiscriminating precedent, nor a yielding to

the clamor of party zeal in behalf of a votoprif^ leader; but

the heartfelt admiration and gratitude of a great people for

the manly virtues and noble patriotism of an unpretending

youth from the ranks of the people. Its sincerity and earn-

estness are the more to be appreciated, as it is so spontaneous

and irrepressible.

Joseph Reeder Troxell Gordon was born January 3d,

A. D. 1844. He was a very slender child in his infancy, and

brought up to boyhood with great care and many fears lest

the forces of his natural constitution would never rally to

strength and maturity. He early indicated more than com-

mon powers of mind, especially in the particularity of his

observations of whatever came under his notice. It w T as this

fact, in his future development, which made him of such essen-

tial service in his connection with our army. At two years

of age, lie discovered — what many artists have failed to no-

tice — that the step of the elephant is differeut from that of

any other dumb brute, and precisely like a man's. His child-

ish descriptions of passiug events were always reliable in the

general and in the particular. He was, early in his childhood,

accustomed to systematic employment of his time. His aid

in, the domestic economy was most remarkable, at a very early

period of his childhood; and, as early as in his eighth year, he

was charged with the sole expenditure for the table of the

family; and has preserved in his own hand the monthly ac-

count of current expenses of his father's family, until the

family was broken up — an instance most remarkable of his

thorough discipline, filial love and precocious character.

During his thirteenth year, he became very much interested

in the labors of his father upon the great political issues of

the day, especially the questions arising upon the repeal of

the "Missouri Compromise;" and, with unwearying assiduity,

devoted himself to reading, and copying, and carefully arrang-

ing the public documents of the Government for his father's

aid in his work. He has preserved many hundreds of pages

of this work, carefully arranged, filed and classified- — a mon-

ument to his industry and discipline, more valuable than the

triumphs of political ambition, or of the strife for wealth.

From the commencement of the great political battle of

1856, he became a steady and an interested reader of the po-

litical news of the day; and was earnest to fully understand

the real issues involved in the battle. He acquired a knowl-

edge, greatly in advance of his years, upon the political econ-

omics of the contending parties of the time. This familiarity

with current political history he maintained to the last. In

the last political struggle, he fully comprehended the dangers

in which the country was involved; and, though a minor, gave

his mind and his heart to the success of Mr. Lincoln, with a

zeal that has found its highest manifestation in the cheerful-

ness with which he has sealed his faith with his blood.

His habits of reading were not exclusive. He was rather

choice than miscellaneous in his reading. He was fond of the

older poets; of History; and read, with peculiar pleasure,

Virgil, Horace, and the Illiad. During the time he was con-

nected with the University, his standing in the classical de-

partment, was always with the first; and in deportment with-

out a blemish. In Mathematics he stood fair, and in the natural

sciences, especially in Geology,* high. In composition and

debate he had but few superiors. His talents and character

won for him, the esteem and affections of the whole faeulty,

and of his fellow-students.

His filial love and devotion, I have no power to exagerate,

if I can adequately portray them to you. His love for his pa-

rents was so marked and unwavering as to have won universal

admiration. The circumstances of his home early made him

a companion of his mother, to whom she was accustomed to

express her joys and griefs with the greatest freedom, and

with the most lively appreciation by him. His father's con-,

nection with public life, necessarily took him much from home,

and Joseph became his mother's affectionate, dutiful, consid-

siderate and devoted friend. At the period of life when the

sports of boyhood, the sights and excitements of a city, the

love and favoritism of his associates, and especially the in-

fluence of their unrestrained liberty and freedom from all care,

would naturally have made him impatient of any restraint,

such was his love for his parents, and especially for his mother

when alone, that he never sought his own pleasure when it

was in his power to contribute to the immediate comfort of

home. He readily took on the habit and character which a

fond and faithful parent would impress. He most cheerfully

and uncomplainingly encountered all the vicissitudes of the

family, at whatever cost to his plans or his pleasures. He

was tender, gentle, and delicate in all his manner and address

to his mother; reverent and admiring of his father. He took

deeply to his heart every word of disrespect and violence

thrown at his father, in the heat of political strife; and gave

himself heart and hand to the vindication of the principles by

* He studied Geology at home, of his own choice. It was not one of bis

University studies. — J. W. Gordon.

•which he felt his father was controlled. He made the most

zealous and untiring efforts to minister to the happiness and

comfort of the family, that his father might feel at liberty to

devote himself to the labors of the sphere he had chosen.

And when sickness, pale and remorseless, began to prey upon

the strength and beauty of his mother's form, he became more

and more a staff and a comfort to her. He performed his

studies at her side, learned to discover and anticipate her

wants, to minister to them with a fidelity and satisfaction to

her most grateful and affecting. As the fearful disease

showed itself more insatiable and relentless, he multiplied his

devotions; and, as month after month wore away, he became

more and more gentle, affectionate and hope ful . No weari-

ness of watching disturbed the equanimity of his temper.

No self-denial was required, that he felt, save as a new intense

on the altar of his holiest devotion. He read to her from the

records of current events, as she was able to bear it ; read to

her from the Sacred Scriptures, in whose light she had walketf

so confidently for many years; and from the weekly issues of

the religious press. He helped her in her great feebleness,

to bear the sacrifice of his father from his home, for the de-

fence of his Government in its imminent peril. He com-

manded every impulse to follow the fortunes of his father in

the battles of his country, while this altar of sacrifice remained

to consume his filial love. By night and by day, mid hope

and fear, with anxieties without and watchings within, he

brought every resource of his being to the accomplishment

of the sacred trust he so cheerfully assumed, of the minister-

ing spirit in her lingering decline. He smoothed the path for

her down the declivities of the grave, removing every stum-

bling-stone, and cheering her in every dark, distressful hour.

Gentle, as the touch of angels, was his hand as he lifted her

wasted form, or wiped her pallid brow of death's chilling

dews. Sweet, as the breath of June, was all his air and mien

in that chamber where she so long held her timid intercourse

with the spirit world. He was the light of love in her eye,

when she had cheerfully yielded the husband of her youth to

6

the call of her country— bleeding from the stab of treason.

He was the joy of her heart, when the air was filled with

shouts and sighs of war, to which he that was her strength

and pride was gone. Watchful, as a guardian angel, he sat

by her pillow through the still nights, that creep so slowly

through their tedious hours, to all save him that burns the in-

cense of love. We would challenge every power of thought,

and every emotion of soul, to praise and honor the filial love,

that turns from every path of youthful pleasure, from every

hour of idle leisure, with a devotion, pure and sacred as earth

ever shows, to take the cares, allay the griefs, and bless the

love of a mother's dying days. Faithful as the shadow to

the substance, and beautiful as an angePs ministry, was his

love to the sainted mother, who now rehearses his numberless

deeds of affection, before the great and admiring hosts of

heaven.

His patriotism was not an impulse — a giving way before

the excitements of military display. He had never been fa-

miliarized with the excitements of noisy and reckless scenes.

He was calm and thoughtful by nature ; but from early boy-

hood had learned to comprehend and enjoy his home, under

the blessings and protection of this benificent Government.

He was faithfully taught to revere the personal and religious

liberty of the Government, to compare his own with monar-

chical liberties. He felt keenly the shame which our nation

has suffered for its enormous system of fraud and oppression

upon the colored people of the land. W T hen but thirteen years

of age, he refused utterly to obey the demands of the ''deputy

marshal" of this State, to aid him in the arrest of a fugitive

slave. To him it was a moral wrong — a violation of the spirit

of the Gospel; and no fear of the possible consequences could

humble him to a violation of his conscience. He was edu-

cated deeply and earnestly to deplore the encroachments of

the institution of slavery upon the liberties of the Govern-

ment, and to revere and love the men who would resist these

encroachments.

In the excitements of 1856, he received the impression that

civil war was imminent, especially if the South should be un-

successful in the election; and from that to his death, had

most heartily sympathized with the Government in its peril.

His enlistment was under circumstances to prove to the world

his devotion to his country; for he was fond of study, and

desirous of an education. The Hon. Cassius M. Clay, of

Kentucky, with whom he was somewhat familiar, and who had

discovered and admired the many traits of worth and real

greatness in him, had made ample provision for his educa-

tion, at his own expense. The door was wide open for him

to realize his highest ambition in this respect. But, in con-

versation with an intimate friend of his, and of his family, he

said that "he firmly believed that he carried, in his constitu-

tion, the seeds of the disease that had laid his mother in the

grave; and that, if he succeeded in acquiring an education, the

chances were against his living to use it with any good to his

country ; and he preferred to serve his country with what

powers he now possessed, in the time of her emergency, rather

than to trust to the future with such a contingency." His

enlistment was duly considered; and all its possible contin-

gencies cheerfully accepted. When he received his father's

consent, conditioned, as it was, upon the irresistible convic-

tion to Joseph's mind, that under the circumstances — his

youth — his prospect for an education — the hopes of his father

that he might live to represent and vindicate his labors with

the coming generation, it was his duty : He received it as

the grateful assurance of heaven's blessings on his solemn

purpose. His motives for joining the army are most satisfac-

torily expressed in his own words, in an unfinished letter, ad-

dressed to his father, and found on his person, after he was

carried off the field of battle. In this letter he says :

" You seem to be at a loss, my dear father, to understand

my motive for volunteering ; but, I think, if you will remem-

ber the lessons, which for years you have endeavored to im-

press upon my mind, that all will be explained. When you

have endeavored, ever since I was old enough to understand

you, to instruct me, not only by precept but by example, that

8

I should prefer freedom to everything else in this world; and

that I should not hesitate to sacrifice anything, even life itself,

upon the altar of my country when required, you surely should

not be surprised, that I should, in this hour of extreme peril to

my country, offer her my feeble aid."

0, noble utterance of a loyal heart ! Worthy of our high-

est praise and honor ! He felt his youth and inexperience ;

but inspired with the holy cause, he felt competent to follow

and execute the commands of the officers over him. He en-

dured the hardships of the camp, of the tedious march, of

personal privation, with the equanimity of experience and

age.

In his actual service, he was early found to possess those

qualifications of mind and heart, which fitted him for the

most important and dangerous duties of the battle field.

His bravery was, when we consider his age and his habits of

life, incomprehensible, but for the light of the motives that

led him to the field. He felt his cause was just; and every

power he possessed, even life itself, must be laid upon its altar.

It will be rarely recorded of any who survive or fall, in all

this terrible war, that he equalled the courage of that beard-

less boy. See him start out at night on those bleak moun-

tains, and dark ravines, sometimes alone, sometimes with

comrades, with the assurance that in almost every thicket,

and behind every log, the remorseless enemy was wait-

ing to shed his blood. See him lead out the scouting

party oftentimes of men double his years; and, with most

fearless heart, put himself into the very midst of the en-

emy. His commanding officer, General Milroy, in his letter

to Joseph's father, conveying the intelligence of his death,

and transmitting his remains, pays him the following tribute

of praise, which I am here permitted to make public. He

" He died as only a brave soldier can meet death, in the

front rank of the battle ; and ' in the imminent deadly breach.'

He had charged up with the foremost of his Regiment, to the

enemy's works ; and with his deadly Minnie had coolly dropped

a rebel soldier on the inside; and re-loaded, and again pulled

trigger with equally deadly effect upon a second traitor, at the

instant a traitor ball pierced him through the brain, as you

will see. I deeply mourn with you the death of this truly

noble boy. Brave almost to a fault, generous as the sun, dif-

fusing joy and animation in every circle in which he moved.

His amiability, afiibility and bravery had endeared him to the

whole of his Regiment; and dearly will the Ninth remember,

and make treason atone for his death, before the war closes.

Having been a member of my military family since the com-

mencement of the present campaign, his many amiable qual-

ities had endeared him to me as a son ; and his death has

created a vacuum in that family which cannot be filled.

" I soon discovered, after my last arrival in Virginia, that

his intelligence, activity and bravery better fitted him as a

scout than an orderly, and accordingly detailed another to

perform the more immediate and onerous duties of orderly;

and permitted him to accompany and to lead scouting parties

almost daily; and he became familiar with every mountain,

valley and path around the enemy's camp ; and had met them in

and upon nearly all of them to their cost. But few soldiers

have met death and danger so often as he has, for the time he

has been in the service."

His General says further : " The day before he was killed,

he was with a scouting party of fourteen, who were ambus-

caded, and fired upon, by a large body of rebels ; and seven

of his companions fell at the first fire — three of them within

three feet of him. The rebel leader sprang out, and demand-

ed of Joseph to surrender, but received for reply the contents

of his Minnie rifle."

From other sources we learn that the evening before the

engagement in which he lost his life, he expressed to the

Adjutant of his Regiment, the strong conviction that he should

be killed; and made all desired disposition of his little effects,

and requested, in case of his death, that his body should be

sent to his father. But his brave young heart did not quail

as the muster-roll challenged him to the field of battle and

10

death. There was no palor on his blooming cheek — no trem-

bling in his limbs — no tears in his eyes ;. but, brave and noble,

as a heart of flesh can be, he faced and fought the foe. A

companion in arms in that terrible charge says, he "was lit-

erally as brave as a lion, and as gentle as a lamb. He fell

early in the action, and close to the enemy's works. He was

the pet of the Regiment, and no death could have occurred

that would have caused more heartfelt sorrow among officers

and men than did his."

But the beloved, the noble youth has fallen. And, while

we deplore the loss of one so brave, so gifted, so worthy of

his patriot ancestors, with whom he now sleeps in the grave,

on which the " dews of heaven weep," and the stars have set

their loving watch till the resurrection morn, with a martial

poet of the Greeks, in his praise of their fallen youthful

braves, we will say of the loved and lost one :

" How glorious fall the valiant, sword in hand,

In front of battle for their native land."

His clear mind, his filial love, his patriotic heart, his deeds

of noble daring for his country's life, will live as long as the

heart can hold the memory of Virtue and Truth. The poet

says:

" But strew his ashes to the wind,

Whose sword or voice has served mankind.

And is he dead whose glorious mind

Lifts thine on high ?

To live in hearts we leave behind

Is not to die.

Is't death to fall for Freedom's right?

He's dead alone that lacks her light,

And murder sullies, in heaven's sight,

The sword he draws.

What can alone enoble fight? —

A noble cause."

My friends, I commend to you the character and the deeds

of the valiant youth whom we delight to honor. He boldly

gave himself to the battle and the death, which we fear awaits

11

many thousands more ere our land shall welcome the return

of peace. The war cloud gathers blackness and tempest still.

Our noble patriots are falling by scores, and hundreds under

the fatal infections of the camp ; and by the fearful shots of

war. The peril to our benificent and glorious Government to

very many minds is as imminent as ever. From a new and

unexpected quarter, the threat of battle is sending fear through

the land. It is possible that necessity will require the doub-

ling of our army in the field, and on the sea. Shall our Gov-

ernment be forced to the hateful work of drafting, while we

have a million of r.oble youth in the land? Will the men of

this Innd — youthful and middle aged — withhold their service

from the most beneficent and Christian Government on earth,

when challenged to save it from the grasp of the most wicked

and remorseless tyranny that ever forged a chain for human

limbs, or plied the faggot to human conscience ? The battle

that is waged against this Christian Government is to break

the power of the condemning conscience of the people, against

the most inhuman, blasphemous, wicked and God-defying vil-

lainy that ever dared to lift its horrid front among the children

of men. Its success would be a greater calamity, a more ap-

palling curse to this fair land and the Christian world than to

extinguish all constitutional liberty, and ask the vanquished

king of Naples to the reconstruction of his throne among us.

Let your minds conceive the thought of an empire on the

American continent, whose fundamental principle should be

the divine right of the stronger to imbrute the iveaker portion of

the race. Conceive the immaculate Jehovah who gave his

eternal Son a ransom to deliver the race from the power and

dominion of sin, and to establish a kingdom of purity, liberty,

and grace among men, attempting to push forward the con-

quests of his kingdom, by the establishment of an empire in

which his own subjects; nay, children, regenerated by his

spirit, and sanctified by his truth, and made heirs of his eter-

nal fullness and glory, are denied their immortality, offered

in sacrifice to the most beastial impurities, and employed to

propagate the guilt of a damning traffic in the bodies and souls

12

of men. It was to aid this Christian Government in resisting

just such an empire as this, in its attempt to overwhelm us in

ruin, that the youthful hero, whose memory and virtues we

honor at this hour, laid aside his ease and earthly hopes, and

went out to the field of battle and of death — " a sacrifice of

nobler name, and richer blood" than ever lay on treason's

hated altar. And as the battle rages, we ask who of all his

youthful companions will make his place good? Who will

take up that death-dealing weapon, which has fallen from his

hands, and bear it with like bravery in this most holy and glo-

rious cause. Let not the thought of your youth make you

weak and irresolute in the hour of peril. To the noble youth

of the State, I commend the virtues and example of the la-

mented dead. In the words of the poet, I take the liberty to

say :

" Leave not our sires to stem the unequal fight,

Whose limbs are nerved no more with buoyant might;

Nor lagging backward let the younger breast,

Permit the man of age, (a sight unblest,)

To welter in the combats foremost thrust,

His hoary head dishevelled in the dust,

And venerable bosom bleeding bare ;

But youth's fair form, though fallen, is ever fair;

And beautiful in death the boy appears—

The hero boy who dies in blooming years:

In man's regret he lives, in woman's tears,

More sacred than in life, and lovelier far,

For having perished in the front of war."

JOSEPH E. T. GOKDON,

DECEMBER 13th, 1861.

BY

MAEY B. NEALY.

Wail, wail, wail,

Ye winds, in the leafless trees !

For the dear young soul, we loved so well,

Floats up on your mystic breeze.

Clash, clash, clash,

war ! with your iron hail ;

For, since his brave young heart is cold,

What man of ye all would quail ?

Weep, weep, weep,

Father, and Sisters now ;

For never again shall a noble flush

Sweep over that pale, pale brow !

Strike, strike, strike !

Ye men with iron nerve :

When ye think of the deeds of this brave young boy,

How could ye ever swerve ?

3

14

For that young life of his

Five foemen's spirits fled ;

But, alas ! alas ! when the day was won,

He lay in the trenches — dead ! >

0, brother to our son,

And friend of our riper years,

It almost seemeth that ye were one,

And these — a Mother's tears !

"Weep, weep, weep,

Father, and Sisters now ;

For never again shall a noble flush

Sweep over that ravished brow !

And weep, my own brave boy,

This friend of thy bright young years ;

For never the death of a dearer joy

Shall drown thy heart in tears.

Toll, toll, toll,

With muffled throats, bells !

For the passing away of as bright a soul

As any on earth that dwells.

So young, so true, so brave —

Earth, unfold your breast !

And give him a sunny and flowery grave ;

And, Heaven, give his soul thy rest.

December 20th, 1861.

A TIME TO ALL THINGS.

Home, 1} o'clock A. M., \

December 9th, 1856. J

Dear Joseph:

The wise man says, "there is a time to all things."

Learn not from this that there is a time for evil deeds, or

words, or even thoughts. It is not so. There is no time for

doing wrong. Here, the wise man is teaching a moral, not an

immoral lesson ; and must be understood as saying, "there is

a time to all just things — to what are right : — and to nothing

else."

Do not forget this. You know by experience, that there is

something for all times. No moment goes by, that has not

some duty, peculiarly its own, to be done. A perfect life,

therefore, requires that everything be done at, and in its own

time : and for this reason : If you put off the duty of the

present hour till the next, it cannot then be done ; for that

hour's duty will then be present, claiming to be done, and it

will have the best right to be done in its own hour. What

right has any hour to put off its own load, and expect another

hour to take it up and carry it ? It is so, too, with different

periods of life. Little children have to grow, and be thought-

less, and innocent, and happy in their innocence. If they are

not happy in their innocence, then they never will be happy

and innocent again. If they are not thoughtless, then they

never will be thoughtless again. Childhood is to each of us

our Eden before the fall. The naming sword will never per-

mit us to return to it again, when our innocence is once lost,

and we are turned out. Life has no other hour after we have

passed from the flowery walks of childhood, that can carry us

back to them again, and enable us to re-live them. Next

comes Youth — life's seed time. It has its duties; and its

trials. The boy's life is the beginning of the man's. If the

It)

boy fails to do his duties, and store his mind with the germs

of knowledge, and virtue, the man must naturally fail to do

his duties, and the whole burthen of duties, left undone in

youth, and manhood, will fall with a crushing w T eight upon

decrepit old age. You know, if the farmer does not sow his

wheat in the fall, he will reap no wheat the next harvest ; and

have no bread for winter. So it is with the youth of our years,

my son. If you sow not the good wheat of knowledge and

virtue now, your manhood will be crowned with no harvest of

plenty and honor ; and your grey hairs will go down in want,

and poverty, and wretchedness to an unmarked, and, it may

be, a dishonored grave.

Now, first of all, Joseph, learn that there is not in youth,

or manhood, or old age, a single moment that has not its

duty — some act that is right and good — to be done. Hence,

you see, if, instead of doing what is thus right and good, you

do what is wrong and bad — tell some false story, or make a

lie — you first cheat the right and good deed out of itis time ;

and lose all that you would have gained in doing it. But that

is not all. The wicked deed — the false word or story — does

more ; it not only steals the time from the right, but it pre-

pares the boy or girl to do other wrongs and tell other false

stories, until life becomes altogether false, and all duties re-

main undone. This makes the extreme bad man, whose end

is always infamous — often terrible.

Dear Joseph, that you may do everything in its own time,

and have no hours, nor days, nor period of life loaded with

the duties of others, left undone, I have written this long let-

ter from my heart of hearts. I ask you to think of the les-

son I have thus given you ; and if you approve it, try and

follow the line of conduct it points out. I have written only

for your good.

In my next I will try and point out your duties, in connec-

tion with their appropriate times. I shall be glad to have a

letter from you ; but more so, to see you do your duties, in

their own times, and well.

Yours truly, J. W. GORDON.

OF PURPOSES

Home, October 10th, 1857.

Dear Joseph:

My time has been so much employed, *in matters

of business, for a long time past, that I may seem to have

neglected — it may be — to have forgotten you. It is not so.

In every condition, and under every circumstance in life, no

one object has been more upon my mind, or close to my heart

than yourself — your education — your well-being and happi-

ness, both now and hereafter. The truth is, you are always

present to my thoughts — sometimes as a source of fear and

sorrow — at others, of hope and delight. You will, therefore,

not think me over solicitous for your development, and the

adornment of your soul with every useful study and habit.

I have already written you a letter in reference to your

appropriation of time to useful and virtuous purposes. I de-

sire now, to fix in your mind the idea of the necessity of ac-

quiring the habit of directing your mind to a purpose. Of

course the purpose must first be formed, and then the pursuit

maintained, until it becomes the habit, both of your mind and

body ; for all practical businesses require both mind and body.

Of course, also, the purpose ought to be such as becomes a

man to entertain and pursue ; or the habit will fall short of

developing virtue — manhood, the only end to be sought as

ultimate or final by a true man.

In the first place, then, of purposes, or designs : There

must necessarily be many, in the life of a man, each of which

will in its turn, claim your attention, tax your energies, mould

your habits, tinge your character, in a word, make you more

or less virtuous — more or less manly. What is to be done ?

18

Shall you take up the affair, the purpose, of to-day, and of

every day of your life, merely on its own account ; and pur-

sue it simply because it is the thing of the time ? Or shall

you not rather form some ulterior purpose, that shall em-

brace, shape and absorb all the occasional purposes of your

life?

In reference to moral questions, and all questions are so,

shall you not say first, and labor to the last to make it good :

" My first purpose, — the great, all embracing purpose of my

life — shall be to do everything which is right for me to do."

Within this rule, all other purposes, proper to be thought of

by you, will be found to lie ; under it, to be modified and con-

trolled.

In determining this general rule, you determine no less in

favor of others than yourself; for whatever it is right for you

to do, will conduce most to promote the well being of others —

the world at large, and will most develope and exalt your own

manhood. Nay, further, it will most honor your Creator ;

for His will is the Right which you purpose, under this rule,

to do. Thus, it is the best selfishness ; the best socialism ;

and the best religion, in the world, to do right. It meets

both extremes — the one and the all — the individual and the

universal, and embraces, and fitly unites the middle.

" But what is right for me ? " you will ask. It is not a

little difficult — if at all possible — to answer your question.

It merits a trial, however, and I will take care that if my an-

swer is not final and absolute — it shall at least, tend to lead

you toward the final and absolute, and not away from it.

All morality is born of knowledge ; and knowledge is truth

in the mind. It implies a knower. And wherever there is a

truth and a knower brought together, until the knower's con-

sciousness recognizes the truth, there, knowledge is born.

Truth is its father, the conscious soul, its mother. The wise

mind, is fruitful of knowledges — the foolish, barren. The

children of the former rise up to bless it— the latter is cursed

with everlasting sterility and nothingness.

The whole universe is, to the mind of a being who knows

it, only a great truth. It is so to the mind of the Creator.

19

We become more and more like Him, as we more and more

know the truth which makes His consciousness.

The Eight for you, implies knowledge co-extensive with

your abilities and opportunities ; and, then, that you should

be industrious to the extent of your capacity; just to the ex-

tent of your relations ; religious to the extent of your faith ;

and truthful in all things.*

I will write soon on the subject of the right.

Yours truly, J. W. GORDON.

* While in Western Virginia, I wrote to Joseph a letter which, I think, con-

tains a better definition— more practical — of the relatively right which each

human being ought to observe in his conduct and life, than this ; and, there-

fore, place it here :

"Grafton, Virginia, June 28th, 1861.

********

And now, my dear boy, do right. Have a purpose in life ; and pursue it

with a will. Let no other man deter you from doing what you know or be-

lieve to be right. Pleasure, pastime, everything will end in disappointment

and pain, if sought at the expense of your own self-approbation. In a word,

labor to know what is right always; and remember that what you believe to

be so, at the time you are required to act on any subject, is right for you, at

that time, whatever it may be absolutely, or in the opinions of others, or even

of yourself at another time.

I am, as always, yours truly, J. W. GORDON.'

NEW YEARS-1861.

Indianapolis, Indiana, ^

25 min. before 12 o'clock midnight, V

December 31, 1860. J

Joseph R. T. Gordon —

My Dear Son: I begin this letter in the year

1860; not, probably, to finish it before the beginning of the

year 1861. If I do not, it will become the bridge, over whose

arch, I shall walk, in conscious thought, from the year that

" is passing and will pass full soon " to the next, which is now

as rapidly advancing toward us. I shall pass this bridge with

joy; for my heart is full of the light of my love for you — a

love which anticipated your birth, and gave you to my hopes

and arms, in the rapture of dreams, in the bright beauty of

innocent childhood ; and which has ever since remained to me

amid the rough bufFetings of the world, the surest talisman

against despair.

The bells tell me the old year is dead ; and the new one

born. It is now 1861. You have been carried a-past the

mile-stone that marks the beginning of a new mile in the

journey of life, in one of the cozy sleeping-cars on Time's

railroad. I have been watching our progress ; and thinking

of the past, the present, and the future of you, my fellow-

voyager. It is a good time to think of such things, but al-

ways better one should do it for himself than for another.

1st. What of your past ? What have you done — ill or

well — good or bad ? What have you failed to do of good, that

you have had time and opportunity to do ? How much have

you grown — ill or well — in the right or wrong direction?

What good purpose have you followed, making its practice

easy by confirming custom into habit ? Or what bad habit has

21

neglect, or evil intent, or easy consenting goodness of heart

strengthened and confirmed, until it has become more and

more your lord and master ; and capable of more and more

easily thwarting your resolutions in favor of a nobler and

higher life? If you find yourself still little advanced in

knowledge, and virtue, and little built up and strengthened

and confirmed in manly and virtuous habits, whose control

over your life becomes more easy and complete every day ;

and if, further, you find that the neglect of duties, and the

following after idle pursuits, and the vain dissipation of your

time and powers upon idle books and vain company, have al-

together made the steady pursuit of those studies which you

once designed to pursue, more difficult than ever before, and

when you do attempt still to pursue them, their acquisition a

matter of less facility and satisfaction, than at some time in

the past, then, I think, you will agree with me, that it is high

time to break off such courses as have thus far led only to

evil — present and prospective ; and to direct your powers to

such studies and labors as you design shall form the business

of your life. I invite you, therefore, to search out the ene-

mies of your progress in the past ; classify them according to

the degree of their power to work you evil, which you have

learned, if you have reflected upon their and your past ; and,

then make war — a war of extermination — upon each and all

of them, dealing your exterminating blows to each in a degree

of severity corresponding to its power of evil to you. This

I know, is a difficult task ; but it is as necessary as difficult.

Its difficulty arises from the fact that any habit of the mind

or body which has great power over us, destroys our capacity

to master and control it, just in the ratio of its own increase

of strength ; and this it effects in two ways : 1. By the aug-

mentation of its own power, which makes it a stronger power

to contend with. 2. By the diminution of your powers of

the mind, or body, or both, which you must bring against it,

and which leaves them, therefore, less capable for the conflict.

Nevertheless, all habits, whether of mind or body, must be

destroyed sooner or later, if their tendency be to evil ; or

4

22

they will ultimately destroy both mind and body, and them-

selves therewith ; for, in this respect, vices are like parasitic

growths upon the body of any living being. They destroy

themselves in working out, as they do, the destruction of the

life which feeds their life. Every moment lost, therefore, in

assailing an evil habit or passion, renders its extirpation more

difficult, until at last all effort ends in idle resolves. An evil

habit, which if attacked with manly resolution to-day, would

succumb and disappear with ease, will, perhaps, be able to

laugh at a stronger resolution to-morrow; and the day after

will carry its miserable thrall to the grave ; or — which is still

more to be dreaded — to infamy.

2d. The present, then, is the time to abandon bad habits ;

and begin to form good ones. It is the only moment in which

such efforts have any promise of success. If it be painful and

difficult to succeed to-day, it will be still more so, if not quite

impossible, to-morrow. Every hour of neglect, and worse,

of indulgence, carries you toward the coast of the Impossible,

where all the sons of men whose motto has been, or shall

hereafter be, " I can't," have been, and will continue to be,

stranded and lost. There sleep the fools who have idly played

with the white sea foam of passion or appetite to-day, to be

whelmed beneath its more than stygian blackness to-morrow ;

and an echo — half in sorrow, half in scorn — ever comes out

from the rocks of that fatal shore, as if to warn the shoal of

coming victims to their own follies and crimes, still repeating

the fool's motto, " I can't."

You must, then, direct your powers backwards at the foes

which tend to drag you backwards and downwards until you

become the bondman of the flesh — the slave of passion and

appetite ; and forwardt toward the friends that beckon you

upwards toward the True, the Beautiful, and the Good — those

grand Idealisms which have been the pilot stars set out in

Heaven to conduct mankind to its eternal glories and beati-

tudes. These friends and foes are alike near and within your

own nature. All other friends, all other foes, are as nothing

for help or hurt to your life and soul, in comparison with

23

with those which contend "upon the arena of your own heart,"

for its direction, and empire. The battle of the Universe is

fought in the heart of every man and woman, wherein all the

powers of Hell and Heaven contend for the possession of the

field. The human will in each sits arbiter, "to judge the

strife," and sways the contest as it lists. And herein lies the

dread power of the will— the origin of Right and Wrong—

of praise and blame — of responsibility.

3d. In the future, I ask you not to dissipate the strength

you have on unworthy objects. Limit your efforts to the

preparation of yourself for that business in life you intend to

follow. Bring your powers to a single point. By means of

the fire-glass, which concentrates the sun's rays, fire is kin-

dled therewith. If you would kindle the world, and make it

blaze with new ideas of use, beauty or goodness, or even with

admiration for yourself— a worthless object— you must con-

centrate your faculties upon some point serviceable to men,

and honorable in their opinion. In the selection of a business,

I would recommend only that it be some pursuit in which the

exercise of your faculties as an instrument, a means — which

professional service always is— should, if possible, conduce to

the development of yourself as the end ; and, indeed, the

highest and only true end of all intellectual effort and train-

ing worthy of the name of education.

And now, my dear son, I invite you to run with me another

stadium in the race of improvement and life. I am, in the

course of time and nature, seemingly much nearer to the goal

than you ; but we know not which of us shall reach it first.

Nor, if we make it a race of improvement and virtue, a gen-

erous strife and emulation as to which shall best run and most

excel therein, need we care ; for he, whose life has been so

employed, must be secure against evil, not only in this state

of being, but in all others beyond, to which death may con-

duct him.

I wish you a happy New Year ! and many happy new years,

when this new year and other unborn years shall have become

old ones ; and that you may so live that each new year's dawn

24

may meet you a wiser, better, happier man than its predeces-

sor, and, with new firmness of heart, making new resolves to

strive more earnestly than ever before for something in life

more excellent still, than you may have known. So shall the

first dream of my heart for you become reality, and, in life or

in death, I shall be content.

I am yours truly, J. W. GORDON.

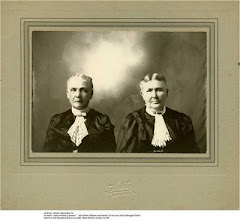

PORTRAITS.

Fort Independence, Boston Harbor. Mass., \

August 25th, 1861. J

Dear Children :

This is the second Sunday I have spent here. I

have taken my quarters at the Fort, and live wholly here.

I have all your pictures with me ; and keep them setting

up before me, on the table where I work. So, my dear chil-

dren, I think of you all the time. I am sure you will think

often of me. I want you to think, also, af what I am going

to tell you; and, if I never see you again, you will thank me

for it. I have been brought to think of what I shall tell you,

by your own dear pictures, as they stand before me — all in-

nocence and sweetness. It seems to me like the little girls

who made these beautiful shadows upon the glass for me to

look at, when I cannot see themselves, must be innocent and

good. There is not the mark of any mean word or wicked

deed upon the face of any one of your pictures. You look

to me like you had always been good and loving to each other,

and to every one else.

Let me tell you what your dear, innocent pictures make

me think of. It is this : It is said that, a long time ago,

there lived a great painter, who spent his whole life in paint-

ing portraits. He could paint portraits accurately, and de-

lighted to do it. Once he desired to paint the prettiest,

sweetest, happiest face in the world. So he went about look-

iug after it. At last he found a bright-eyed, happy, innocent

child, and painted its face, as the prettiest, sweetest, happiest

face he had ever seen. He was then a young man himself,

when he painted that picture ; and every one thought it the

26

most beautiful picture in the world. It was so innocent — so

pure — so happy — God's image, without a stain or a shadow.

Now, after a long time, when the painter had grown to be

very old, he still kept on painting portraits ; and one day-

concluded that as he had painted the prettiest, sweetest, hap-

piest face in all the world, when he was himself young and

happy, he would before he died seek out, and paint the ugli-

est and most miserable face he could find. He would, in this

way, leave the prettiest, most innocent and happy face, and

the ugliest, most wicked and unhappy face, in all the world,

side by side, in strong contrast with each other. He accord-

ingly sought out and found the ugliest, most wicked and un-

happy face he had ever seen, and painted it, and set it up be-

side the portrait of the beautiful, innocent, happy child, whom

he had painted when he himself was young and happy.

Every one felt startled and pained by the contrast. It was

like placing an angel just from Paradise, on whose path no

shadow had ever fallen, by the side of a fiend from the infer-

nal pit, whose life had been passed amid the darkness, and

crimes, and sorrows of that unhappy world. The one was,

indeed, the picture of a good angel — the other of a wicked

one. But people would continually ask whose pictures these

were. Every one desired to know that. And whose do you

think they were ? My own dear children, will you believe me

when I tell you, that both these portraits were drawn for one

and the same person ; that the pretty, innocent, happy child,

whose face was so much like an angel's that people almost

mistook it for one, grew to be that ugly, wicked, unhappy

man, whose face was so horrid, that people thought it the face

of an infernal fiend ? It was really so.

The change, from the beautiful and innocent child, to the

horrid and wretched man, all took place in a few years. A

short lifetime was long enough to change the sweetest crea-

ture in the world to the foulest — the happiest to the most

wretched. Would you believe such a change possible ? If

any one of you could only be convinced that you would change

so, and become so ugly and wicked, would you not rather die

27

now, than live to see yourself become so hateful? I am sure

you would. You could not endure the thought of so horrible

a change from what you are, without a wish to die sooner

than undergo it. I could not, much as I love you.

Now, what produced the change ? What made the pretty

child grow up into the ugly man ? There must have been

some cause for so sad a change ; and you ought to know what

it was. I will tell you what it was. It was a course of wick-

ed words and deeds, that did it all. It may have begun to

take place very early in life. The first shade cast upon the

bright, sunny face of the beautiful child, may have been the

shadow of some false story, or some naughty act of disobedi-

ence, or expression of ill temper, that seemed so trifling as to

leave no stain at all. But, although unseen by human eyes,

it did leave a stain which the eye of God saw, and which the

child's conscience both saw and felt. The next falsehood, or

evil deed, darkened the first shadow, and the next made it

darker still. Another, and another followed, until the beau-

tiful soul became overcast with the blotches and ugliness of a

thousand crimes ; the light of innocence and happiness passed

away forever, to make room for the darkness, and guilt and

wretchedness that supplanted them. It is in this way that all

ugly, wicked, wretched people are made. Little children are

never very ugly ; and they are almost always so innocent and

good, that we love to see them, and love them, because they

really are lovely. God is good to all children; and, having

made them innocent and happy, has given them bright eyes,

and dimpled features, that all who see them may feel and

know that they are happy and sinless — happy because they

are sinless. But the child's features are all soft and pliable

to the influence of the soul, which acts constantly upon them

and changes them, so that they constantly express its charac-

teristics more or less distinctly. If the child grows up in in-

nocence, it will have a face that will tell it to all the world, in

plainer language than words, and as true as the soul of inno-

cence itself. Be good, therefore, and your faces will ever

bear witness to your goodness before men, as your consciences

28

will before yourselves and God. On the other hand, be wick-

ed, false, vile, and your light will become darkness ; your

faces, the indexes of the characters you form, will become

ugly ; and all the world will at length learn and know how

wicked you have been. I hope I shall never shudder to look

on the picture of one of you, when I shall place it by the

side of the beautiful ones now before me. Be good children,

and then you will grow brighter and happier always ; and,

even when you become old, the light of childhood's innocent

beauty will still adorn your features ; for the beauty of happy

childhood will only have ripened into that of thoughtful old

age. Remember, whenever you are tempted to do wrong,

that wrong is the ugliest of the soul ; and that, sooner or

later, the soul impresses its own features on the body. If the

soul is hateful — loathsome, it is not in human power to pre-

vent the body from becoming so. Remember, my dear chil-

dren, the story of the painter, and his two portraits. Do

not live so that you may become ugly in crime and guilt, and

their attendants shame and sorrow, as you now are beautiful

in innocence and goodness, and their attendants honor and

promotion.

I wish you to keep all my letters ; and read them often. I

am sure' they are written for your good ; and, I think, will

tend to produce right habits of thougnt and action, if you will

only remember them.

jjc^c % %. %. %$:*%.

I ask you to write me a pretty letter ; and that you love

one another.

I am yours truly, J. W. GORDON.

IMMORTAL LIFE.

Fort Independence, Boston Harbor, Mass., \

September 8th, 1861. /

My Dear Children :

It is Sunday evening again ; and I again sit down

to talk to you for a short time. I wish you were here to talk

to me, that I might see your happy faces, and we could both and

all be happy again together. But although I cannot be with

you in person, yet you know that I am in heart and soul. You

do not see me, yet you know that I am still living, and that,

although absent from you, I still love you, and labor to make

you happy ; and prepare you for usefulness, by securing to

you the advantages of a good education. Now, dear children,

why do you believe that I am still alive, that I love you, that

I am thinking of you, and working for you? Is it because you

once saw me, and know that I did labor for your happiness, and

wished you to become wise and good ? If that is the reason,

then, you can believe that your dear Mother is still living,

still thinking of you, still watching over you, and caring and

praying for your welfare and happiness ; for you know how

good she was, in all the offices of kindness and love while she

staid with you. She has not changed in her heart more than

I. She is only absent, like I am from you — perhaps not so

far off as myself. She is still your Mother, ever loving, and

watching over your goings and comings, and caring for your

welfare and happiness as if she was present with you. Now,

if you can believe that I am doing all I can for you, you can

just as easily believe that your Mother, who was always kinder

than I, is still alive, and doing all her loving heart can prompt

for your safety and happiness.

But you may say : " We could believe all this if Mother

5

30

could only write to us and tell us so, as you do ; or, if Mother

had not died." But, my dear children, if I had lost both my

hands, and could not write, you would still think I was living

to love you ; and, even if my tongue was cut out, so that I

could not talk to you. All this would make no difference.

It is not, then, because I can still write and talk to you, that

you think I still live and love you. You would believe it just

as much if I could do neither — if my hands and tongue were

both dead. So you see, that hands and tongue are no part of

your father ; for you would think me none the less your liv-

ing, loving father, if I had neither. It is not, then, my writ-

ing a letter to you, that makes you believe that I am still

alive ; nor even my having hands to write with, and a tongue

to talk with. If my tongue and hands were dead, you would

still think of me as your loving father. So that you see, af-

ter all, that my hands and tongue are no part of me ; but only

my instruments, given me by the Great and Good Being, who

created us all, in order that therewith I might write and speak

to you.

My hands, indeed, are no more a part of me — of my soul —

my very self — whom you love and call father, and think of as

father, than my pen is. Both are my mere instruments ; and

I may lose both at any time, and still live to love you. Now,

there is no difference in this respect between my tongue *and

hands, and my ears and eyes. Tongue, hands, ears, eyes, in

a word, all the organs of this body of mine, are only instru-

ments given me by my kind Creator, any one or all of which,

I may lose, and still remain the same living, loving soul you

love, and call Father. True, I could not communicate with

you after such a loss, as now before it ; because you have no

means to receive communications, except such as can only be

addressed by these organs of mine. But when you shall

have lost your bodily organs, then you and I will have become

alike again — both spirits — and then we shall be able again to

communicate to each other, our loves and our hopes, our joys

and our sorrows, far more easily, and plainly, I trust, and

31

pleasingly also, than we can now do, by means of words either

spoken or written.

Now, if you can only remember what I have said — that my

hands, tongue, eyes, ears, and all my senses may be destroyed;

and I yet live, and be none the less your father than before

I lost them ; then you will know of a truth that this body of

mine is not me, but only my instrument ; for, if this body

was me, then every time I might lose a finger, or a hand, an

eye, or an ear, I should cease to be myself, and be only a frag-

ment of myself. But you never think of a person who has

lost his or her thumb or finger, as any less the person after

the loss, than he or she was before it happened. You know,

for instance, that your Grandfather has lost his thumb ; but

you know that he is still your Grandfather, just as much as

he was before he lost his thumb. So you think ; and so he

both feels and knows ; and so, in fact, he is. If, then, the

loss of a part of the body, leaves the soul still alive and per-

fect, why should it suffer more from the loss of another part,

than the first ? In truth it does not ; but as your Grandather

could never write so well after, as before, he lost his thumb,

so each new loss of the same kind destroys in a degree the

soul's instruments for communicating its thoughts and feelings

to other souls in bodies, until, at last, when the whole body dies,

the medium of communication between the soul whose body is

thus dead, and other souls whose bodies are not dead, is alto-

gether destroyed. So it is with your Mother and you. She

is still your living, loving Mother, as truly to-night as she

ever was in her life before ; but her instruments for telling

you so, are lost to her— dead. But you know that the instru-

ment and its owner are never one and the same. The one

owns the other ; and the owner is always greater and above

the thing owned. For instance, the owner always has power

to direct, control, and use the thing owned.

I would be just as good a penman without my pen as with

it ; but I could not write a word without it. So, when you

shall have learned to play on the piano, the house may take

fire and burn down, and destroy your piano ; but you will still

32

be none the less musicians than you were before you lost your

instrument. Just so it is with your dear, absent Mother.

She has only lost the instruments by means whereof she once

filled your little souls with the music of a Mother's love and

goodness. But you know that love and goodness are no part

of the body, any more than sound and music are part of the

piano. Love and goodness come from the soul, just as the

tune comes from the soul of the musician. The piano, or

other instrument, is but his means of giving it utterance — ex-

pression. There are thought, passion, soul in the music ; but,

when the sound has died away on the instrument, there is

neither thought, passion nor soul in the instrument. The tune,

with all its stirring and delightful combinations, is immortal ;

but the instrument on which it was once sounded may at any

moment become ashes. So is the soul which formed and gave

life to the tune. It lives forever ; and none the less, after the

body which was once the instrument, on which it sounded ill

or well the anthem of life, has been resolved into dust, than

before.

I am sure you will think of these things; for, by doing so un-

til they become plain and familiar to your minds, you will be

able to learn and know of a truth, and hold as your best

and noblest possession, the truth that each soul must 7ieeds be

immortal ; and that the friends whom we now miss, as dead,

are only absent. The medium of communication between

them and us has been destroyed. Death has cut the tele-

graphic wires — their poor human nerves — on which their

loves, and hopes, and fears were once transmitted from them

to us, as ours were from us to them. Let us, then, rest in

the faith which, in me, is knowledge, that, when it shall be for

our advantage, the great Creator will re-establish communica-

tion between us, and the loved and lost, whom, not as dead,

but absent only, we mourn ; and, again, the love which we now

miss will return, and fill our hearts " with lightning and with

music." Till then, let us rest in hope.

* * * # ^ * * >jc *

I have tried to get you to think of your Mother ; because

33

I know, if you will, you will be as good and loving to each

other as she always desired you to be ; and that you will obey

your Grandfather, and Grandmother, and your Uncle James,

heartily.

* * * ******

Write to me often ; and always think of me, as I am

Yours truly, J. W. GORDON.

WE MUST HAVE FAITH.

Fort Independence, Boston Harbor, Mass., )

September 15th, 1861. /

My Dear Children :

I have been thinking of you all week. It has

brought Sunday again, and now I will talk to you about what

I have seen and thought of, so that you may have some ad-

vantage from it as well as myself. I have no other thing to

think of, or labor for, but your welfare and happiness ; and I

hope that, although I cannot see you any more, you will still

believe that I am thinking of you almost continually, and of

what is best for you. It is on this account that I have writ-

ten such long letters, in order to get you to thinking about

yourselves, and how important it is to do right.

I do not know that you can understand my long letters. I

hope, however, you can. If you cannot, at first, you will

when you get older. I ask you to keep these letters, and

read them once every month, or so; and think of what I say

in them; and you will soon understand them, and will be paid,

I think, for your trouble. I am sure they will aid you to

think of what most concerns you to understand ; and what is,

unfortunately, least understood by most people.

I hope you will remember what I wrote you last week,

about your Mother's being still alive and watching over you,

although you do not see her any more. I think you will both

understand and believe what I told you on that subject. I am

sure it is true ; and feel that it is necessary to our happiness

to think so. Nor is this the only case in which we must hold

as certain what we cannot see, or feel, or know anything about

through our senses. You think that I am just as much alive,

and just as much interested in your welfare, as if you saw

me every time you go to breakfast, dinner, or supper, as you

35

used to do, when your Mother got our meals ready for us,

and called us to them with such loving words and sweet wel-

comes.

I know you trust me, and think that I will find you a place

to live, and books, and a teacher, so that you may learn to be

wise, and good, and happy. Nor shall your trust in me be

ill placed, if I live.

Well, just as you trust me, so you trust others whom you

do not see. You trust the people of China for tea ; and the

people of the South for sugar and coffee ; and, when you get

these articles, you feel perfectly confident that there is no

poison in any of them. Now, you have never seen these peo-

ple ; but you still believe that they exist, and that they will

not put poison into your tea, sugar and coffee. You not only

believe that they exist and act ; but, also, that their lives are

subject to, and controlled, like yours, by a sense of right and

wrong ; in other words, that they will naturally and habitually

prefer to do you good rather than harm — to give you tea, su-

gar and coffee, without poison, to nourish and strengthen you,

rather than with poison, to injure and destroy you. And just

so it is with other things that you do not see.

When you go to bed at night, you do not feel afraid that

any one will hurt you while you sleep. On the contrary you

feel perfectly certain that all the people in the world, whether

you know them or not, will suffer you to sleep safely until

morning. You feel and almost know that there is some un-

seen power that controls all people ; and makes them prefer

to allow you to sleep securely, rather than to disturb and hurt

you. Nor do you feel any less certain when you lie down,

that you will wake up again, and find day-light and sunshine

instead of darkness and night. You trust some Being whom

you have never seen to bring back the sun in the morn-

ing. You know, too, that you can trust that Being just

as well as if you saw Him every day, moving the sun

round the heavens, to give you day-light and darkness. So

you have to trust some Being whom you have never seen,

to enable you to wake up again in the morning, when you

go to sleep at night ; for it is even more wonderful, if vou

36

will only think of it, that, when you lie down in sleep

and forget everything — even that you yourselves exist —

you should, without any difficulty or trouble, be able to rise

up in the morning, and think again of what you were doing

when you went to sleep ; and take it up again, where you left

it at night, and finish it, just as though you had never been

interrupted by night and sleep at all. The truth is, my dear

children, we all have to believe a great deal more than we can

see, or absolutely know by our senses — seeing, hearing, tast-

ing, smelling and feeling — to exist. We must have faith in

what is beyond us, and above us. We must believe in what

is greater than we are ; for we have to rely on such a power

continually, whether we will or not. We have to trust our-

selves to the goodness and greatness of such a power all the

time ; for without it we would not be able to " live, move, or

have our being" for a single moment. He gives us air to

breathe, or we would die at once. He gives us light, or we

should be unable to enjoy any of the beautiful and glorious

sights of the universe. In a word, He gives us all that we

have, or can conceive of, as necessary to our happiness as rea-

sonable beings.

But you may, perhaps, say: "The air, and light, and all

those other good gifts of this great Being, are mere matters

of course — exist everywhere as matters of necessity." Not

so, however, or they could not be taken away from anywhere.

They would always be found wherever we may be called to go.

But they are not. Bad men can shut off the light, and, there-

by, all that is beautiful to sight, from their victims, whenever

they have the power, as they frequently do. Wicked men

have often done this ; and in some parts of the world are do-

ing so to-day. So they can shut off the air, and kill the poor

people over whom they have the power, out-right. The light

and air, then, do not exist as necessary and absolute bless-

ings, dependent upon themselves only for existence ; but they

are dependent upon some power greater than, themselves,

which gives and controls them — giving them in one place,

and withholding them in another. We must, then, believe in,

37

and rely upon what we do not, and cannot see. We must trust

ourselves wholly to the wisdom and goodness of some Being

greater than we can comprehend, and better than we can con-

ceive of ; and it is all the same whether we acknowledge our

trust in Him or not. The wickedest man trusts Him as much

as the best, and, indeed, more ; but he is too wicked and mean

to acknowledge his trust in Him ; or even that He exists.

Now, let me tell you how I was led, at this time, to think

of our daily and hourly trust in the power, wisdom, and good-

ness of some Being whom we do not, and cannot see, or know

anything about by our senses. It was in this way : The other

morning, as I was going up the harbor, in a little boat, I

passed through among a great many large ships, that were all

lying at anchor there. Seeing them all lying still, though the

wind blew strong against them, and the waves beat upon them,

I asked myself: "What holds these vessels in their places ? "

I said in answer : "Their anchors." Then I looked, and saw

an anchor-chain going down from the bow of each ship into

the sea ; but I could not see the anchor nor the bottom of the

harbor in which it had taken hold of the firm earth, and there-

by held the ship, so that neither the winds nor the waves could

move it out of its place, nor drive it against the shore. Then

I said to myself: " These ignorant sailors trust themselves to

that which they do not, and cannot see, and of which they

can know nothing at all, except by faith. They have, per-

haps, never been down at the bottom of the sea ; but they

believe, nevertheless, that the sea has a bottom, and that they

may rely on it to hold their anchor, so that their ship may

rest securely, notwithstanding the winds and the waves. It

may be that no strong diver has ever told them that the sea's

bottom was firm ground. They believe it, however; because

they deem that some firm bottom is necessary to contain the

water of the sea itself. Without something more than water,

they could not believe that the sea could remain together.

Now, just so it is," said I to myself, "with each man and each

woman in the world. Every human soul is, like a vessel float-

ing on the great sea of the universe. It must have an anchor

6

38

to hold it, and prevent its dashing against its fellows, or against

the shores, and going to ruin. What is its anchor? What

chain holds it? And what is the bottom of that sea in which

its anchor fastens, and holds it securely from harm and ruin ?

The anchor of every human soul is Hope; its anchor-chain

Faith in the Unseen Container of all things — the Great Being

who fills and sustains the whole visible and invisible universe.

Every man, or woman, who is worth anything to himself, or

herself, or the world — every one who is safe from going to

ruin for a single moment, must be anchored by an undoubting

trust in the Great and Good God, whose nature is the bottom

of our sea — the bounds and shores of our universe. All our

actions have relatio to Him; and none the less so even if we

deny that He exists. We may never think of Him at all, yet

thoughtlessly we must rely upon Him; or, thinking of Him,

and denying Him, we must still rely upon Him; or, last and

best, we must think of Him, reason about Him, and His wis-

dom, goodness and power, and trust Him with a perfect knowl-

edge of His nature, just as the man who has gone down to the

bottom of the sea trusts it, when he throws his anchor into it,

with a perfect knowledge of its nature. The Thinker is the

diver who goes down, and up, and every way to God, through

' the visible and invisible things of creation.' Such would I

have you, my dear little girls. Any human being who does

not thus go to his or her Creator, falls short of his or her

privileges — falls below the end for which he or she was cre-

ated. Our true birth-right and happiness is thus to know

God, and trust Him wisely and entirely."

You owe this long letter to my seeing the ships at anchor.

If you understand it, both you and I shall be happy in it —

you in reading it, I in writing it. Read it over often, and

think of it ; and you will understand it. Since Joseph has

volunteered, I am more anxious for you to become well edu-